It’s been a year of drive-through birthday parties, Zoom meetings in the same room as your three-year-old’s virtual preschool class, and feeding everyone in the house what sure feels like infinite meals and snacks. Every. Single. Day.

Now that the next stage of pandemic parenting is upon us, you might be wondering what you can do to support your young child’s learning. Our answer? Sing with them! (Seriously. That’s it.) Like everything we do here at Music Together®, our suggestion is rooted in research. Let’s take a look behind the scenes and explore how making music supports brain development and socio-emotional learning, two areas you just might be thinking about right now.

Music: The Brain Builder

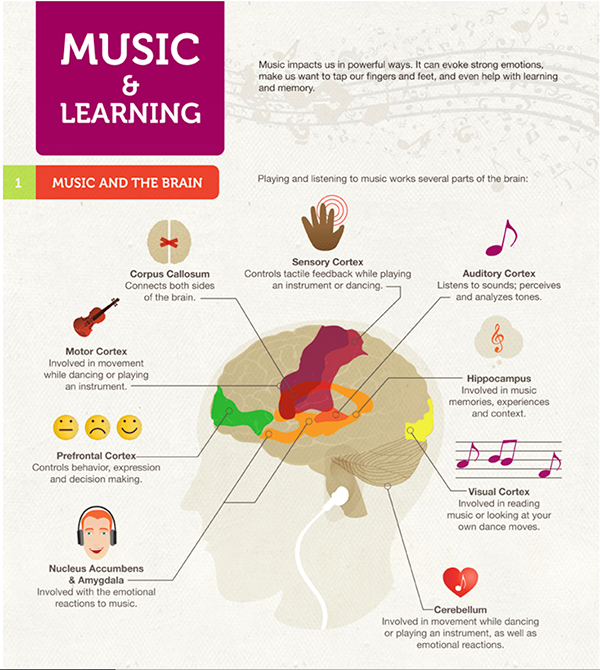

We’ve all experienced a mood boost when we belt out a ballad while driving or have a hairbrush mic-drop moment. It’s (literally) because of our brains! Singing increases production of dopamine and serotonin, the so-called feel-good and happiness hormones. It also puts many of our brain regions to work, strengthening our neural pathways. Neural connections are kind of like our nervous system superhighways, and they’re formed through our experiences and habits. When we take part in activities that strengthen them, it’s easier to learn and grow throughout our lives.

For young children, whose brain architecture is forming, music-making can be even more impactful. You see, by our mid-twenties, our neural pathways are pretty much done being built, but they’re just coming together for babies and toddlers. In fact, our brains are more active during the first five years of life than they will ever be. Positive early experiences create strong neural pathways—and a strong foundation for all future learning.

Here’s how music acts as a brain architecture superhero. Because music is accessible and enjoyable for young children, they are likely to repeat songs they like over and over (and over), especially when the grownups they love sing with them. This repetition and engagement exercises important neural pathways, making them stronger and supporting the development of a sturdy brain foundation. And all you have to do is sing!

Building Community Connections

Think back to the last time you sang or danced with a group. Maybe you danced the “Electric Slide” at a wedding? Sang at an outdoor Music Together class? Joined in a sports chant with other fans at a stadium? Even if it’s been a while (and we get that!), you probably remember the bond you felt with those around you, even if they were strangers.

Back to the brain to help us understand what’s going on. Remember those neural pathways? Turns out that sharing music experiences with others can activate similar neural connections in all participants’ brains. This synchronization leads to those feelings of togetherness we remember long after the event. The brain connections also foster positive social interactions and increased empathy within the group.

And adults aren’t the only ones who feel this; so do young children! In fact, research suggests that active music-making with others supports many parts of socio-emotional development, including self-regulation, self-confidence, leadership skills, social skills, and more.

In one studyi, preschoolers who engaged in joint music and movement activities showed greater group cohesion, cooperation, and prosocial behavior when compared to children who did not engage in the same music activities. This increased empathy and commitment (e.g., feeling of “we”) was theorized to emerge from the shared intentions and collective goal of singing and dancing together. Even in infancyii, adult-child music and movement interactions can lead to increased rhythmic AND emotional coordination and connection. Researchers propose this might support infants’ earliest abilities to engage in positive social interactions with others. Cool, right? And . . . all you have to do is sing!

As you can see, simply singing with your children does so much for them. In addition to being a stress reliever and energy builder for everyone, making music supercharges learning. (That’s why we like to say Music Learning Supports All Learning®.) What we’ve covered here is just the beginning. If you’re looking to learn more about music and early learning, find more right here on the blog and, if you are enrolled in class, your Music and Your Child guide. (Ask your teacher if you need a new copy.)

There’s a lot we don’t know about how this academic year is going to go, but one thing is certain: Singing, dancing, and jamming with the little ones we love helps them develop a lifelong love of music—and develop a strong foundation for all future learning.

References

i Kirschner, S. & Tomasello, M. (2010). Joint music-making promotes prosocial behavior in 4-year-old children. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31, 354-364.

ii Gerry, D., Unrau, A., & Trainor, L. J. (2012). Active music classes in infancy enhance musical, communicative and social development. Developmental Science, 15(3), 398-407.

Cirelli, Jurewicz, & Trehub (2018). Musical rhythms in infancy: social and emotional effects. Cognitive Neuroscience Society, 25 Annual Mtg, March 24-27, Boston

Cirelli, L.K., Einarson, K.M., Trainor, L.J. (2014). Interpersonal synchrony increases prosocial behavior in infants. Developmental Science. 17:6, pp. 1003-1011.

Darrow, S. & Levinowitz, L.M. (2020). Supporting Your Child’s Learning with Music [Webinar] Music Together Worldwide. https://www.musictogether.com/blog/supporting-your-childs-learning-with-music/.

Kirschner, S., & Tomasello, M. (2009). Joint drumming: Social context facilitates synchronization in preschool children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 102, pp. 299-314.

Williams. K.E., Barrett, M.S., Welch, G.F., Abad, V., & Broughton, M. (2015). Associations between early shared music activities in the home and later child outcomes: Findings from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 31, pp. 113-124.

Winsler, A., & Koury, A. (2011) Singing one’s way to self-regulation: the role of early music and movement curricula and private speech. Early Education and Development, 22: 2, pp. 274-304.